New Paragraph

"If, as a young girl, a palm reader were to tell me what was to come of my life, I might be tempted to laugh. But, my kookom would never let me do such a thing, she had higher expectations of me than that. Showing respect was important to her: I honoured, and continue to honour her teachings"

whale bones and boxcars

Churchill, Manitoba is my hometown, the Polar Bear capital of the world. It's the only prairie, harbour town in Canada and sits at the end of the Hudson Bay rail line. Flanked on one side by the Churchill River and the other by Hudson's Bay, I was heavily influenced by its teaming waters of hundreds of Beluga whales that came up the river to calve every summer, and the foreign freighters that lined the dock waiting to be filled with grain by the weary worn boxcars. I wrote my first poem here. It was about this magnificent river where I watched my elders set and pull nets as a child. It must have been a gooder as my mother looked pleasantly surprised when I read it to her. One might have called me a dreamer back then. And, I very likely was! Days spent running along the rocks, eating tundra blueberries while watching the bobbing Beluga whales

among the incoming freighters.

comfortable lines

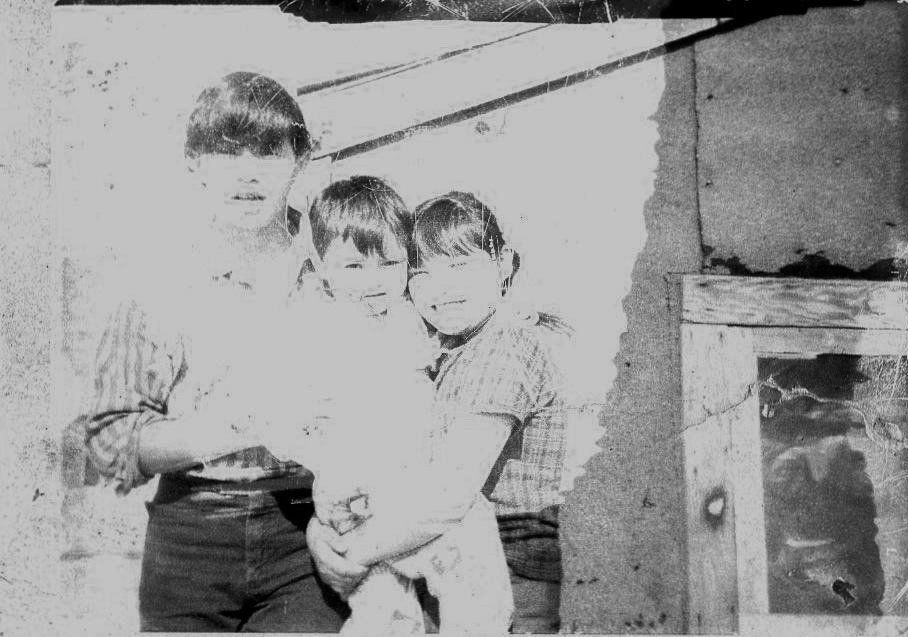

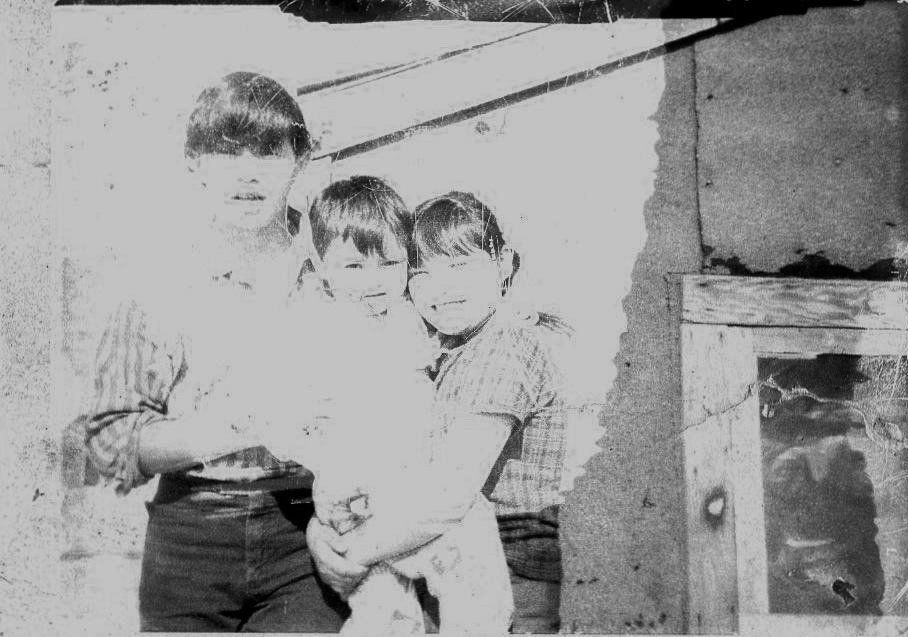

Raised by my grandmother and mother, I learned my Cree culture early by listening to Cree stories and watching my kookom, pluck geese, skin fish, tan hides and do beadwork. Every Saturday the train would bring our trapper relatives in from their traplines to load up on supplies for the following week. They often came directly to our house where my granny would have kettle-coffee and hot bannock waiting. There they would sit catching up in our tiny kitchen. The Cree language is low on adjectives, but strong on verbs. This makes it a very visual language so stories play out on a giant internal movie screen.

I loved listening to them talk and laugh.

skin off our noses

My uncle was a traditional hunter. His hunting forays would fill our kitchen with Caribou, the odd Fox, Muskrat or other wild game. This kept us through the long Winters. My grandmother never wasted anything. In Fall she would make duvets and pillows from the down of the wild fowl, in Winter, a Fox tail turned into our hood trims that protected us from the windy blasts that would have stung the skin off of our noses without. Moose hide became mukluks and mitts that were adorned by her masterful beadwork. She and my mother worked hard. Both women were also employed as "laundresses" by the military and their long day jobs gave us ample time to go exploring the shield, pools and mossy coves in summer, and jumping into the deep snow drifts in Winter. Although I have many wonderful childhood memories of my hometown,

I also have some hard ones.

tongue tied

Our town and family did not escape the negative effects of alcohol and all the ugliness that goes along with it. I know now that my people were hurting from the effects of government imposed decisions that prevented them from practising and living their culture. It didn't help that racism was open and rampant at that time. There was a palpable fear of the police, teachers and those in positions of authority. I remember wondering why we were treated lesser-than just because our ways were different. We were fun to be around in my mind. Our people were hearty. They loved to laugh, tell funny stories, and worked so hard. The government also created divisions among us. Residential school policies meant that many of my friends

and relatives would have to say good-bye and board the train for residential school. I remember clearly standing on the platform seeing their faces in the windows as the train pulled away from town. I was spared residential school because the government stripped my grandfather of his status when he enlisted to serve. When my grandmother married him, she too was stripped of her status. Anyway, the town felt sad after the kids left. It felt empty. There were tears of anger that often time spilled out into violent outbreaks. Those are hard memories. The relations between the Cree and the Sayisi Dene were also affected by government policy. The Dene who were relocated to Churchill by the government were basically abandoned there and left to survive in deplorable conditions for decades. There were a lot of deaths and tears among the Dene, and the Cree, caused by this unnecessary imposed trauma. As a result, my siblings and I were encouraged to learn more of the non-indigenous culture, including a proficiency in English. It was regrettably thought by our parents that it would make our lives easier, and be to our our advantage. I am now attempting to relearn my language.

the move

The closing of the military base left many of the towns people without work. This included my mother and grandmother. Knowing that there would be no well paying jobs in town, and refusing to go on welfare, my mother packed us up and moved us south to the capital city of Winnipeg. Moving to the city was a culture shock. I missed home; the rocks, the waves, laughs with friends and family. We knew few indigenous families and it was lonely. Not finding immediate work found us living in the inner city and eating at the Salvation Army soup kitchen. Main Street seemed to be the only place where anyone else looked like us. It was in Winnipeg that I learned my first three guitar chords, sang in coffee houses, and met some pretty good musicians. Life eventually got better. Mom's determination, and my grandmother's masterful beadwork enabled us move out of the inner city to a more safe neighbourhood.

silver-lined moccasins

My mother, with a grade eight education struggled to earn her social work degree, but she did. She later moved us back up north to Thompson. This is where granny left us for the other side. Mom lived, worked, and retired as a social worker in Thompson. She held the same position with the provincial government for over thirty years. We laid her to rest in that town that she grew to love. These were two very inspiring and hard working indigenous woman. They left an indelible mark on me, my siblings, and cousins. They taught us that life will have its struggles, but that quitting wouldn't get us where we wanted to be. My brother followed in mom's footsteps and became a social worker, my sister is a Health Policy Analyst with the federal government. I earned my MBA and use it to further my work as a Singer-songwriter. I'm grateful for the teachings of these two wonderful women and walk proudly in their moccasins.

the trc & me

During those years my guitar never left my side. I had been doing more media writing than songwriting back then but, the stories I lived were all waiting to be told. It's been said that our experiences culminate into who we are, that our lived experiences shape our world view. Well, this was mine. My people are hearty, kind, funny, and enduring. Something that most people don't get to see. This is why I do what I do. I open the lid on our human side, introduce you to some hard-working people, and tell of information that you may not know. My most memorable performing experience was performing for residential school survivors at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Hearing in Edmonton. I had spend days listening to their stories, shed many tears, and even had a lot of laughs. It was then that I knew I had to do more as a writer. I wanted to work toward healing and inclusion with my music.

I do believe that the truth will set us free. Already, the discovery of mass and unmarked graves at residential school sites has us all talking, and trying to find ways to gain what we all lost through the creation of Canada as two islands. There are many things that I have left unsaid, suffice to say that these experiences were the impetus for five albums and two singles. As an indigenous woman I want to share with you so that you too, can understand, know and move forward together with us.

Ekosi.

whale bones and boxcars

Churchill, Manitoba is my hometown, the Polar Bear capital of the world. It's the only prairie, harbour town in Canada, and sits at the end of the Hudson Bay rail line. Flanked on one side by the Churchill River and the other by Hudson's Bay, I was influenced by its teaming waters of Beluga whales that came up the river to calve every summer, and the foreign freighters that lined the dock waiting to be filled with grain by the weary worn boxcars. One might have called me a dreamer back then, and, I very likely was! Days spent running along the rocks, eating tundra blueberries while watching the bobbing Beluga whales among the incoming freighters. Definitely an incubator for dreams.

comfortable lines

Raised by my grandmother and mother, I learned my Cree culture by listening to my grandmother tell Cree stories and watching her, pluck geese, skin fish, tan hides and do beadwork. Every Saturday morning trapper relatives came in on the train from their traplines to load up on supplies for the following week. They often came directly to our house where my granny would have kettle-coffee and hot bannock waiting. There they would sit around the old wood stove catching up in our tiny kitchen. The Cree language is low on adjectives, but strong on verbs. This makes it a very visual language so the stories I heard played out on a giant internal movie screen. I loved listening to the elders talk and laugh.Their deep-lined, leathered faces were so beautiful to me. I felt so safe around them. I wrote of this time in

Morning Laughter.

skin off our noses

My uncle was a traditional hunter. His hunting forays would fill our kitchen with Caribou, the odd Fox, Muskrat or other wild game. This kept us through the long Winters. My grandmother never wasted anything. In Fall she would make duvets and pillows from the down of the wild fowl, in Winter, a Fox tail turned into our hood trims that protected us from the windy blasts that would have stung the skin off of our noses without. Moose hide became mukluks and mitts that were adorned by her masterful beadwork.

hung out to dry

My grandmother made her living as a washerwoman. She worked very hard. She washed clothes for the town elite by hand, after hauling water from the river, and heating it on the old wood stove. She would then hang the clothes out on the line to dry, then iron it all with the stove-heated iron. I wrote of her days as a Washerwoman in

Washerwoman's Lament. Her life taught me to not quit when life was hard. I rarely heard her complain. She just kept going. My mother quit school in grade 8 to help her. I think mom quitting school was her way to get away from what she experience there. Her memories of school weren't positive ones. Anyway, later mom and granny became employed as "laundresses" by the military, giving them better wages and less manual labour. Although I have many wonderful childhood memories of my hometown, I also have some hard ones.

tongue tied

Our town and family did not escape the negative effects of alcohol and all the ugliness that goes along with it. I know now that my people were hurting from the effects of government imposed decisions that prevented them from practising and living their culture. It didn't help that racism was open and rampant at that time. There was a palpable fear of the police, teachers and those in positions of authority. I remember wondering why we were treated lesser-than just because our ways were different. We were fun to be around in my mind. The government also created divisions among us. Residential school policies meant that many of my friends and relatives would have to say good-bye and board the train for residential school. I remember clearly standing on the railway station platform, looking up, and seeing their faces in the windows as the train pulled away from town. I was spared residential school because the government stripped my grandfather of his status when he enlisted to serve. When my grandmother married him, she too was stripped of her status. Anyway, the town felt sad after the kids left. It felt empty. There were tears of anger that often time spilled out into violent outbreaks. Those are hard memories. The relations between the Cree and the Sayisi Dene were also affected by government policy. The Dene who were relocated to Churchill by the government were basically abandoned there and left to survive in deplorable conditions for decades. There were a lot of deaths and tears among the Dene caused by this unnecessary imposed trauma. As a result, my siblings and I were encouraged to learn more of the non-indigenous culture, including a proficiency in English. It was regrettably thought by our parents that it would make our lives easier, and be to our advantage. I am now attempting to relearn my language.

the move

The closing of the military base left many of the towns people without work. This included my mother and grandmother. Knowing that there would be no well paying jobs in town, and refusing to go on welfare, my mother packed us up and moved us south to the capital city of Winnipeg. Moving to the city was a culture shock. I missed home; the rocks, the waves, laughs with friends and family. We knew few indigenous families and it was lonely. Not finding immediate work found us living in the inner city and eating at the Salvation Army soup kitchen. Main Street seemed to be the only place where anyone else looked like us. Main Street was a tough place at night, but by day it wasn't as bad. I wrote of our time spent on

Main Street

on

Main Street,

a song on Fathomless Tales from Leviathan's Hole. The days of Main Street were hard, but it taught me what I wanted, and what I didn't want. It was in Winnipeg that I learned my first three guitar chords, sang in coffee houses, and met some pretty good musicians. Life eventually got better. Mom's determination, and my grandmother's masterful beadwork enabled us move out of the inner city to a more safe neighbourhood.

silver-lined moccasins

My mother, with a grade eight education struggled to earn her social work degree, but she did. She later moved us back up north to Thompson. This is where granny left us for the other side. Mom lived, worked, and retired as a social worker in Thompson. She held the same position with the provincial government for over thirty years. We laid mom to rest in that town that she grew to love. I felt like an orphan for a long time after she died. I wrote of how I missed in

Where Time Stands Still. These were two very inspiring and hard working indigenous woman. They left an indelible mark on me, my siblings, and cousins. They taught us that life will have its struggles, but that quitting wouldn't get us where we wanted to be. My brother followed in mom's footsteps and became a social worker, my sister is a Health Policy Analyst with the federal government. I earned my MBA and use it to further my work as a Singer-songwriter. I'm grateful for the teachings of these two wonderful women and walk proudly in their moccasins.

the trc & me

During those years my guitar never left my side. I had been doing more media writing than songwriting back then but, the stories I lived were all waiting to be told. It's been said that our experiences culminate into who we are, that our lived experiences shape our world view. Well, this was mine. My people are hearty, kind, funny, and enduring. Something that most people don't get to see. This is why I do what I do. I open the lid on our human side, introduce you to some hard-working people, and tell of information that you may not know. My most memorable performing experience was performing for residential school survivors at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Hearing in Edmonton. I had spend days listening to their stories, shed many tears, and even had a lot of laughs. It was then that I knew I had to do more as a writer. I wanted to work toward healing and inclusion with my music.

I do believe that the truth will set us free. Already, the discovery of mass and unmarked graves at residential school sites has us all talking, and trying to find ways to gain what we all lost through the creation of Canada as two islands. There are many things that I have left unsaid, suffice to say that these experiences were the impetus for six albums and two singles. As an indigenous woman I want to share with you so that you too, can understand, know and move forward together with us.

Ekosi.

whale bones and boxcars

Churchill, Manitoba is my hometown, the Polar Bear capital of the world. It's the only prairie, harbour town in Canada, and sits at the end of the Hudson Bay rail line. Flanked on one side by the Churchill River and the other by Hudson's Bay, I was influenced by its teaming waters of Beluga whales that came up the river to calve every summer, and the foreign freighters that lined the dock waiting to be filled with grain by the weary worn boxcars. One might have called me a dreamer back then, and, I very likely was! Days spent running along the rocks, eating tundra blueberries while watching the bobbing Beluga whales among the incoming freighters. Definitely an incubator for dreams.

comfortable lines

Raised by my grandmother and mother, I learned my Cree culture by listening to my grandmother tell Cree stories and watching her, pluck geese, skin fish, tan hides and do beadwork. Every Saturday morning trapper relatives came in on the train from their traplines to load up on supplies for the following week. They often came directly to our house where my granny would have kettle-coffee and hot bannock waiting. There they would sit around the old wood stove catching up in our tiny kitchen. The Cree language is low on adjectives, but strong on verbs. This makes it a very visual language so the stories I heard played out on a giant internal movie screen. I loved listening to the elders talk and laugh.Their deep-lined, leathered faces were so beautiful to me. I felt so safe around them. I wrote of this time in

Morning Laughter.

skin off our noses

My uncle was a traditional hunter. His hunting forays would fill our kitchen with Caribou, the odd Fox, Muskrat or other wild game. This kept us through the long Winters. My grandmother never wasted anything. In Fall she would make duvets and pillows from the down of the wild fowl, in Winter, a Fox tail turned into our hood trims that protected us from the windy blasts that would have stung the skin off of our noses without. Moose hide became mukluks and mitts that were adorned by her masterful beadwork.

hung out to dry

My grandmother made her living as a washerwoman. She worked very hard. She washed clothes for the town elite by hand, after hauling water from the river, and heating it on the old wood stove. She would then hang the clothes out on the line to dry, then iron it all with the stove-heated iron. I wrote of her days as a Washerwoman in

Washerwoman's Lament. Her life taught me to not quit when life was hard. I rarely heard her complain. She just kept going. My mother quit school in grade 8 to help her. I think mom quitting school was her way to get away from what she experience there. Her memories of school weren't positive ones. Anyway, later mom and granny became employed as "laundresses" by the military, giving them better wages and less manual labour. Although I have many wonderful childhood memories of my hometown, I also have some hard ones.

tongue tied

Our town and family did not escape the negative effects of alcohol and all the ugliness that goes along with it. I know now that my people were hurting from the effects of government imposed decisions that prevented them from practising and living their culture. It didn't help that racism was open and rampant at that time. There was a palpable fear of the police, teachers and those in positions of authority. I remember wondering why we were treated lesser-than just because our ways were different. We were fun to be around in my mind. The government also created divisions among us. Residential school policies meant that many of my friends and relatives would have to say good-bye and board the train for residential school. I remember clearly standing on the railway station platform, looking up, and seeing their faces in the windows as the train pulled away from town. I was spared residential school because the government stripped my grandfather of his status when he enlisted to serve. When my grandmother married him, she too was stripped of her status. Anyway, the town felt sad after the kids left. It felt empty. There were tears of anger that often time spilled out into violent outbreaks. Those are hard memories. The relations between the Cree and the Sayisi Dene were also affected by government policy. The Dene who were relocated to Churchill by the government were basically abandoned there and left to survive in deplorable conditions for decades. There were a lot of deaths and tears among the Dene caused by this unnecessary imposed trauma. As a result, my siblings and I were encouraged to learn more of the non-indigenous culture, including a proficiency in English. It was regrettably thought by our parents that it would make our lives easier, and be to our advantage. I am now attempting to relearn my language.

the move

The closing of the military base left many of the towns people without work. This included my mother and grandmother. Knowing that there would be no well paying jobs in town, and refusing to go on welfare, my mother packed us up and moved us south to the capital city of Winnipeg. Moving to the city was a culture shock. I missed home; the rocks, the waves, laughs with friends and family. We knew few indigenous families and it was lonely. Not finding immediate work found us living in the inner city and eating at the Salvation Army soup kitchen. Main Street seemed to be the only place where anyone else looked like us. Main Street was a tough place at night, but by day it wasn't as bad. I wrote of our time spent on

Main Street

on

Main Street,

a song on Fathomless Tales from Leviathan's Hole. The days of Main Street were hard, but it taught me what I wanted, and what I didn't want. It was in Winnipeg that I learned my first three guitar chords, sang in coffee houses, and met some pretty good musicians. Life eventually got better. Mom's determination, and my grandmother's masterful beadwork enabled us move out of the inner city to a more safe neighbourhood.

silver-lined moccasins

My mother, with a grade eight education struggled to earn her social work degree, but she did. She later moved us back up north to Thompson. This is where granny left us for the other side. Mom lived, worked, and retired as a social worker in Thompson. She held the same position with the provincial government for over thirty years. We laid mom to rest in that town that she grew to love. I felt like an orphan for a long time after she died. I wrote of how I missed in

Where Time Stands Still. These were two very inspiring and hard working indigenous woman. They left an indelible mark on me, my siblings, and cousins. They taught us that life will have its struggles, but that quitting wouldn't get us where we wanted to be. My brother followed in mom's footsteps and became a social worker, my sister is a Health Policy Analyst with the federal government. I earned my MBA and use it to further my work as a Singer-songwriter. I'm grateful for the teachings of these two wonderful women and walk proudly in their moccasins.

the trc & me

During those years my guitar never left my side. I had been doing more media writing than songwriting back then but, the stories I lived were all waiting to be told. It's been said that our experiences culminate into who we are, that our lived experiences shape our world view. Well, this was mine. My people are hearty, kind, funny, and enduring. Something that most people don't get to see. This is why I do what I do. I open the lid on our human side, introduce you to some hard-working people, and tell of information that you may not know. My most memorable performing experience was performing for residential school survivors at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Hearing in Edmonton. I had spend days listening to their stories, shed many tears, and even had a lot of laughs. It was then that I knew I had to do more as a writer. I wanted to work toward healing and inclusion with my music.

I do believe that the truth will set us free. Already, the discovery of mass and unmarked graves at residential school sites has us all talking, and trying to find ways to gain what we all lost through the creation of Canada as two islands. There are many things that I have left unsaid, suffice to say that these experiences were the impetus for six albums and two singles. As an indigenous woman I want to share with you so that you too, can understand, know and move forward together with us.

Ekosi.

Phyllis Sinclair Music resides on Treaty 6 territory, the traditional home and gathering place of the Cree, Saulteaux, Blackfoot, Metis, Inuit, Dene and Nakota Sioux. We acknowledge those peoples who shared, and cared, for these sacred lands since time immemorial to allow for our lives and livelihoods.

Phyllis Sinclair, Songkeeper Woman

ᓂᑲᒧᓇᐦ ᑲᑲᓇᐍᓂᑕᐠ ᐁᐢᑵᐤ

2024© Phyllis Sinclair